Traditional wood fired ovens were widely distributed throughout Paris. The retail bake shop was very visible and located at street level with display windows along the sidewalk. The engine that ran and supplied all the baked goods was in the basement where natural conditions provided a darker cooler space in which to work. With a fire in the oven, however, the basement did not stay cool and the work environment, as the photos following will show, was quite warm. These black and white vintage photos were gifted to me thirty or forty years ago perhaps by Helen and Jules Rabin who toured Europe looking for information on how to build a bake oven and start their own bakery (Upland Bakery) in Vermont a few decades ago.

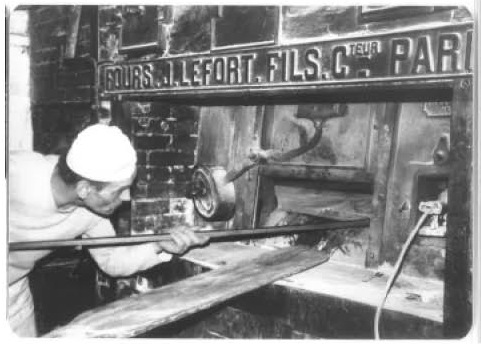

Although Maine Wood Heat imports oven cores from Fayol, the world’s oldest oven company, and I have seen many commercial indoor and outdoor village bake ovens in parts of France further East, I have never had the chance to visit a traditional cellar based wood fired oven in Paris. The photos are not of high quality but they are worth sharing to show some details of two traditional ovens’ firing and baking techniques, and because the photos also nicely display the real world work environment and conditions and focused work of the underground bakers of Paris. Upstairs, a nicely dressed female clerk (perhaps the baker’s wife), sells the finished baked goods. In the cellar, at one oven, the baker, clad only in white shorts and simple shoes, mixes and shapes the dough, loads the oven, and pushes load after load of bread products through the oven. In the second bakery, the veneer of the oven is a bit more rugged and carried the name of the oven builder, J. Lefort. Sons, on its cast iron banded face. The baker working this oven wears baker’s whites, including a cap for his head. The traditional underground ovens shown here are round inside a square brick veneer layout. The dome, you can see, is extremely shallow or almost flat, and one would assume exerts considerable lateral thrust. In all shallow arch rectangular ovens that I am aware of, the lateral thrust of the oven ceiling is contained by very heavy vertical iron bars spaced evenly apart and running along the outside left and right walls of the oven exterior opposite the arch. Below the hearth and above the arched dome, long sturdy threaded metal rods connect to the exterior vertical castings and contain the thrust of the oven.

I once crawled through a coal fired oven in Lewiston, Maine one week before it was demolished along with the entire building. The floor of the Lewiston oven was 14′ x 14′ but the two front corners were of little use since they could not be reached with a peel. The Lewiston, Maine oven featured the exterior heavy steel vertical bars and the long restraining rods above the arch and below the hearth. When the building and oven were demolished, I asked the wreckers if they could save all of the oven castings for me and they did, including a very large and heavy counter weighted loading door, the massive cast iron round coal grate and the heavy cast iron coal firebox loading door and the ingenious lighthouse revolving cast iron fixture that allowed the baker to turn the light fixture briefly into the oven and then turn it back out away from the intense heat to protect the light bulb in the fixture. In the Lefort oven you can see a light fixture port to the right of the loading door.

The traditional round French and Paris oven design has a bit more structural integrity than a rectangular oven design as each circular course is laid up. In the round design the inaccessible front corners of the square oven hearth design are also eliminated. The exterior face of the Paris oven shows some very heavy cast iron banding along with the loading door for the oven, the firebox door and the large clean out doors at the top and it would appear that this banding also plays a role in tying the exterior structure together, which is constantly being stressed by the expansive forces of the hot oven inside which would not have had the advantage of the high density and very effective insulation materials that we use today in our standard ovens.

The firebox for the oven in Paris is under the front center of the oven. When the oven needs a refreshing charge of heat and fire in the oven, the baker lifts up a heavy cast iron hood, shaped like a welder’s helmet, with a long steel rod, and places the hood (called a Gueulard), in a metal ring on the front center tile of the hearth and after stoking the fire below, directs the flame into the oven through the Gueulard. The Gueulard has a big eye on the rear of the hood where the baker can hook his rod into the eye and swivel the Gueulard in any direction to direct the flame to which ever part of the oven needs more heat. Low in the rear ceiling of the oven at the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions are typically a pair of flue exits. Long guillotine dampers can be opened or closed above each of these flues with long rods passing though the oven and emerging on the front upper face of the oven veneer. The flues extend over the oven dome to add more heat to the mass as they pass over the dome and have large clean outs for soot removal on the top front face of the oven. The baker has no infrared gun or built in thermometer to measure the oven temperature. He does this with his eye, sense of the length of the burn, the volume of wood, and with his hand. In the famous Poilâne bakeries of Paris, each oven has a fire in it continuously, and the baker works a six hour shift (four bakers total in a twenty four hour day). The Poilâne baker can check the oven temperature with a small piece of paper placed in the front of the oven. By observing how quickly it browns he can determine if the oven is at the proper temperature. When visiting one of our favorite bakeries, Moulin d’Arche, near the home town of Fayol in T’ain L’Hermitage, we watched a young baker call in a more experienced baker who was in the kitchen just across the stone paving from the huge pair of direct fired ovens. The head baker came out and placed his hand just inside the door for a second or two, then turned to the younger baker and instructed him to burn for five more minutes before raking out the very ample coals.

In Paris, once the oven has been adequately recharged for the next load or more bread, the baker can remove the Gueulard and replace the cover in the ring, and redirect the remaining flame from the fuel charge underneath the oven, where it can enter the flues now from behind the oven. The flues from the two rear positions in the oven dome which travel up over and forward across the oven, have clean out ports. The clean out doors for these flues on the Lefort oven are square castings. The clean out doors on the second boxer-short-baker oven are oval and look to have been a replacement set. At the center of each door is a knob, likely attached to dampers to regulate the draft in each flue. In the Lefort oven, the two flues, likely come together and exit opposite the central clean out door.

Clear shots of the oven show the very heavy cast iron front retaining band at the front of the oven with the oven builder’s name (Lefort and Sons) cast elegantly into the band. Finding a foundry today in most places able to do a casting of this size is almost impossible, so diminished has the demand for iron castings become. When I first visited Finland in 1978 and toured the foundry that made the doors for our masonry heaters, the same foundry was making eight foot diameter sewer pipes. The hardware castings for doors assembled in Finland today, are now cast in Germany. On Martha’s Vineyard in Edgartown along the harbor entrance sits a gorgeous three story lighthouse. The lighthouse which is twelve feet or more in diameter at its base, was cast in iron panels for some location on the mainland and many years ago was disassembled and moved to Martha’s Vineyard. Cast iron lighthouses of this sort are unlikely to be made anywhere today.

It is my understanding that the multi-generational oven building family firms are now almost entirely gone in France. Our own small firm is now engaging a third generation in our work, but I think we are very much the exception today as a company that specializes in custom made artisanal products built one brick, one element, or one weld at a time.

When I first visited France on an oven visit about twenty years ago, we visited many village communal ovens to which people brought their bread on foot, by cart, or wagon. Each oven was shared by the village and precious coppiced fuel was burned to fire the oven and everyone shared the oven space. Signature slashes in the oven doughs going into the oven could identify one owner’s brand from another.

Many of the ovens we visited were over one hundred years old. We visited a chocolate products wood fired bakery near the French Alps and asked the third generation owner how often he had to repair the oven, and he said that it had needed very little repair but in his generation they had flipped the Terre Blanche (white earth) hearth stones over so as to start with a fresh surface for the next generation of baking.

Back in Paris, note how the oven dome seems to have little steps in the circular brick coursing. It is likely that the brick were laid on a sand or wooden form. In the era of high demand for such ovens the dome bricks were a nicely tapered trapezoidal shape that could be laid on a slightly pitched coursing basis in refractory mortar and that every brick would have had a slightly wedging effect relative to the bricks around it. Fayol has confirmed that they would have supplied both the wedge bricks and the floor tiles (both made from Terre Blanche) for these period ovens. We recently replaced two five foot diameter hearth ovens in Freeport, Maine that were about six years old. The domes looked very nice but they were built with standard rectangular firebrick and as some of the mortar between the bricks deteriorated, the bricks began to simply slide into the oven with no wedging effect to stop them. Every firing cycle would of course heat up and expand the bricks and bit and have a corrosive effect on the mortar. After a few years of this expansion/contraction cycle and after the loss of some of the mortar, the domes just started to collapse and slip inward with nothing to do to save them. All we could do was to pull them apart and to replace them with our tongue and grove Le Panyol element design. I have another set of photos in my files showing the assembly of a very large shallow dome for an eight to ten foot diameter circular rotating hearth oven in France. The mason is building the arch with very few supports using custom made fairly small tongue and groove shaped refractory Terre Blanche Fayol bricks and he is laying the bricks in a spiral. Munoz photos below.

First course tipped up slightly with rope shim

First turn of spiral complete

<–Telescoping rods support form plate under arch center

Dome spiral almost complete –>

The pink and white sea shell on my bed side table was also built year by year in a slowly expanding spiral following the universal rules of sacred geometry proportions.

In ancient Florence, the City Fathers and Cathedral Chapter wanted to build a very grand cathedral, but did not want to follow the Gothic designs cathedrals in France. They designed instead a Cathedral with no Gothic features or flying arches and settled instead for a gigantic 150 foot diameter dome to be built on top of the grand church. Unfortunately, when they designed the building, they did not know how to design or build the dome and no one else did either. To save money they knew that the dome so high up in the air would need to be somehow constructed without an internal support, but every proposal given for the dome required such an unaffordable support. One man alone, a goldsmith, who had traveled all over the ancient world, said that he could do the job and that he would only show his technique if he was given the job. There were of course countless naysayers. The designer left no drawings or records of his miraculous construction methods, but over forty years, a single Italian architecture historian slowly unraveled the mystery. The giant eight sided dome was built in a spiral fashion and the bricks were laid in a reinforced herringbone pattern so that shear lines associated with rings of diminishing courses did not occur and he also laid out every brick from rope lines attached to a center point that followed the pattern of an eight sided petaled leaf so that each course dipped a bit in the center transferring the stress downwards rather than inwards to the unfinished center. The dome did not collapse under construction and has never collapsed and supports a massive stone viewing tower above it.

Bread was traditionally mixed by hand in a large dough box. I once had a three foot long antique American bread dough box in my home on legs which had been repurposed by my partner for holding yarn. Even forty years ago, the basement bakeries of Paris had switched to larger dough mixers as you can see.

On the face of the ovens you can see some metal piping for water and in one photo you can see a funnel at the upper left of the photo to the left of the door. This funnel allowed the baker to add a fixed amount of water at the front end of the baking or a new load of bread and this water could enter through the face of the oven and fall by gravity on a pan inside the oven and flash to steam to provide the added moisture that the baker might want. In the nice photo of the large loaf of bread emerging from the oven and being held in the baker’s hand, the baker is thumping the bottom of the load to listen for a correct tone to indicate that the bread is fully baked.

The traditional basement bakers of Paris were not visible to the bread customer. The famous Poilâne bakeries of Paris which use similar ovens, have changed this visibility policy and customers can, with advance permission, get a chance to see the baker and ovens in operation. The wood fired basement bread ovens are at the heart of what Paris has been and is today. Give us this day our daily bread. This is noble and even sacred work. Bakers are critical to our lives and personal and community health. Their hard work and commitment to their calling feeds and answers our prayers. Blessings on the bakers and all the people of Paris.